Rossby wave

Atmospheric Rossby waves are giant meanders in high-altitude winds that are a major influence on weather.[1] They are not to be confused with oceanic Rossby waves, which move along the thermocline: that is, the boundary between the warm upper layer of the ocean and the cold deeper part of the ocean.

Rossby waves are a subset of inertial waves.

Contents |

Atmospheric waves

Atmospheric Rossby waves emerge due to shear in rotating fluids, so that the Coriolis force changes along the sheared coordinate. In planetary atmospheres, they are due to the variation in the Coriolis effect with latitude. The waves were first identified in the Earth's atmosphere in 1939 by Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby who went on to explain their motion.

One can identify a Rossby wave in that its phase velocity (that of the wave crests) always has a westward component. However, the wave's group velocity (associated with the energy flux) can be in any direction. In general, shorter waves have an eastward group velocity and long waves a westward group velocity.

The terms "barotropic" and "baroclinic" Rossby waves are used to distinguish their vertical structure. Barotropic Rossby waves do not vary in the vertical, and have the fastest propagation speeds. The baroclinic wave modes are slower, with speeds of only a few centimetres per second or less.

Most work on Rossby waves has been done on those in Earth's atmosphere. Rossby waves in the Earth's atmosphere are easy to observe as (usually 4-6) large-scale meanders of the jet stream. When these loops become very pronounced, they detach the masses of cold, or warm, air that become cyclones and anticyclones and are responsible for day-to-day weather patterns at mid-latitudes. Rossby waves may be partly responsible for the fact that the Northeast United States is colder than Europe at the same latitudes.[2]

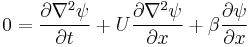

Free barotropic Rossby waves under a zonal flow with linearized vorticity equation

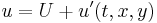

Let us start with perturbing a flow that with only a time and spatially invariant zonal flow U with no meridional component.

We assume the perturbation to be much smaller than the mean zonal flow.

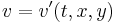

Relative Vorticity  , U and V can be written in the form stream function (

, U and V can be written in the form stream function ( ) (assuming non-divergent flow which stream function completely describes the flow):

) (assuming non-divergent flow which stream function completely describes the flow):

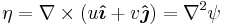

Considering a parcel of air that has no relative vorticity before perturbation (uniform U has no vorticity) but with planetary vorticity f as a function of the latitude, perturbation will lead to a slight change of latitude, so the perturbed relative vorticity must change in order to conserve potential vorticity. Also we make the approximation that  , so the perturbation flow does not advect relative vorticity.

, so the perturbation flow does not advect relative vorticity.

which  , and plug in the definition of stream function to obtain:

, and plug in the definition of stream function to obtain:

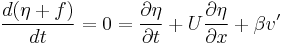

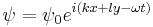

Guess a traveling wave solution with wave numbers k and l, and frequency omega:

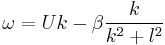

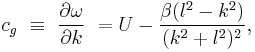

We obtain the dispersion relation of:

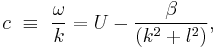

The zonal phase speed and group speed are given by

where c is the phase speed,  is the group speed, u is the mean westerly flow,

is the group speed, u is the mean westerly flow,  is the Rossby parameter, and k is the zonal wave number. The above proves that phase speed is always westward relative to mean flow, but group speed can travel both ways depending on the wave number; large zonal wave number waves (short waves) leads the mean flow, and small zonal wave number waves (long wave) retrogrades. The meaning of large and small only depends on the value of

is the Rossby parameter, and k is the zonal wave number. The above proves that phase speed is always westward relative to mean flow, but group speed can travel both ways depending on the wave number; large zonal wave number waves (short waves) leads the mean flow, and small zonal wave number waves (long wave) retrogrades. The meaning of large and small only depends on the value of  , if

, if  , then the group speed is the same as the mean zonal flow.

, then the group speed is the same as the mean zonal flow.

Meaning of Beta

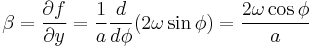

The Rossby parameter is defined:

is the latitude, ω is the angular speed of the Earth's rotation, and a is the mean radius of the Earth.

is the latitude, ω is the angular speed of the Earth's rotation, and a is the mean radius of the Earth.

If  , there will be no Rossby Waves; Rossby Waves owe their origin to the gradient of the tangential speed of the planetary rotation (planetary vorticity). A "cylinder" planet has no Rossby Waves. It also means that near the equator on Earth where

, there will be no Rossby Waves; Rossby Waves owe their origin to the gradient of the tangential speed of the planetary rotation (planetary vorticity). A "cylinder" planet has no Rossby Waves. It also means that near the equator on Earth where  but

but  except at the poles, one can still have Rossby Waves (Equatorial Rossby wave).

except at the poles, one can still have Rossby Waves (Equatorial Rossby wave).

Poleward-propagating atmospheric Rossby waves

Deep convection and heat transfer to the troposphere is enhanced over anomalously warm sea surface temperatures in the tropics, such as during but by no means limited to El Niño events. This tropical forcing generates atmospheric Rossby waves that propagates poleward and eastward and are subsequently refracted back from the pole to the tropics.

Poleward propagating Rossby waves explain many of the observed statistical teleconnections between low latitude and high latitude climate, as shown in the now classic study by Hoskins and Karoly (1981).[3] Pole-ward propagating Rossby waves are an important and unambiguous part of the variability in the Northern Hemisphere, as expressed in the Pacific North America pattern. Similar mechanisms apply in the Southern Hemisphere and partly explain the strong variability in the Amundsen Sea region of Antarctica.[4] In 2011, a Nature Geoscience study using general circulation models linked Pacific Rossby waves generated by increasing central tropical Pacific temperatures to warming of the Amundsen Sea region, leading to winter and spring continental warming of Ellsworth Land and Marie Byrd Land in West Antarctica via an increase in advection.[5]

Oceanic waves

Oceanic Rossby waves are thought to communicate climatic changes due to variability in forcing, due to both the wind and buoyancy. Both barotropic and baroclinic waves cause variations of the sea surface height, although the length of the waves made them difficult to detect until the advent of satellite altimetry. Observations by the NASA/CNES TOPEX/Poseidon satellite confirmed the existence of oceanic Rossby waves.[6]

Baroclinic waves also generate significant displacements of the oceanic thermocline, often of tens of meters. Satellite observations have revealed the stately progression of Rossby waves across all the ocean basins, particularly at low- and mid-latitudes. These waves can take months or even years to cross a basin like the Pacific.

Rossby waves have been suggested as an important mechanism to account for the heating of Europa's ocean.[7]

Bibliography

- Rossby, Carl-Gustaf et al. (1939). "Relation between variations in the intensity of the zonal circulation of the atmosphere and the displacements of the semi-permanent centers of action". Journal of Marine Research 2 (1): 38–55.

- Platzman, George W. (1968). "The Rossby wave". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 94 (401): 225–248. Bibcode 1968QJRMS..94..225P. doi:10.1002/qj.49709440102.

- Dickinson, Robert E. (1978). "Rossby waves - long-period oscillations of oceans and atmospheres". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 10: 159–195. Bibcode 1978AnRFM..10..159D. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.10.010178.001111. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146%2Fannurev.fl.10.010178.001111.

See also

References

- ^ John D. Cox (2002). Storm Watchers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. p. 213. ISBN 047138108X.

- ^ "Winter cold of eastern continental boundaries induced by warm ocean waters". Nature 471 (7340). 31 March 2011. Bibcode 2011Natur.471..621K. doi:10.1038/nature09924. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v471/n7340/full/nature09924.html.

- ^ Hoskins; Karoly (1981). "The steady linear response of a spherical atmosphere to thermal and orographic forcing". J. Atmos. Sci. 38: 1179–1196. Bibcode 1981JAtS...38.1179H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1981)038<1179:TSLROA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Lachlan-Cope, Tom; William Connolley (2006). "Teleconnections between the tropical Pacific and the Amundsen-Bellinghausens Sea: Role of the El Nino/Southern Oscillation". Journal of Geophysical Research.

- ^ Ding, Qinghua; David S. Battisti and Marcel Küttel (10 April 2011). "Winter warming in West Antarctica caused by central tropical Pacific warming". Nature Geoscience. Bibcode 2011NatGe...4..398D. doi:10.1038/ngeo1129. http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ngeo1129.html.

- ^ Chelton, Dudley B.; and Schlax, Michael G. (12 April 1996). "Global observations of oceanic Rossby waves". Science 272 (5259): 234–238. Bibcode 1996Sci...272..234C. doi:10.1126/science.272.5259.234. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/272/5259/234.

- ^ Tyler, Robert H. (11 December 2008). "Strong ocean tidal flow and heating on moons of the outer planets". Nature 456 (7223): 770–772. Bibcode 2008Natur.456..770T. doi:10.1038/nature07571. PMID 19079055. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v456/n7223/abs/nature07571.html.

External links

- Rossby Waves, from the American Meteorological Society

- An introduction to oceanic Rossby waves and their study with satellite data